There is nothing to say about this poem–just buy the book.

There is nothing to say about this poem–just buy the book.

The Age of Iron

When I see an ironing board

folded in the closet of a motel room,

and the iron resting like a sledgehammer on the shelf above,

I think of the Age of Iron

and my mother standing in the kitchen,

folding clothes on the green table,

a bottle if spray starch at her elbow, not even the radio on—

For some reason the memory always

has a faint aroma of brimstone,

for she did not like to iron the clothes

yet somehow had found herself

condemned to this particular hell

where her job was tucking her chin against her chest

to hold a sheet in place as she folded it twice

and then twice more

over and over into eternity.

I remember her looking down

at the flat steel surface of the iron

like an unenchanted mirror,

then spitting to ensure that it was hot,

how in that act she expressed

the essence of her philosophy;

and how one afternoon in the middle of July

she raised the iron

and pressed it firmly against

the skin of her left arm

where it hissed against the tissue

with the sizzle-sound

of bacon frying in a pan.

And that was the greatest speech that I would ever hear

made by a master rhetorician

in protest of the thousand things

that can’t be named

while at the same time it was the breakthrough performance

of an insane but brilliant actress,

who had staged her own kidnapping,

and was in this unique manner

holding herself ransom,

sending a photo of herself

to The New York Times, utterly

confident of its immediate publication

under a boldface

twenty-point headline

that would read: Angry

Wife, Woman, and Mother,

Still Not Free, Burns.

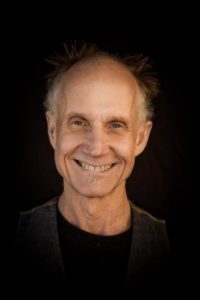

Tony Hoagland, from Recent Changes in the Vernacular, Tres Chicas Press.