Here on Cape Cod, the hurricane is just a summer storm, mostly passed by. I had fallen into a lovely rhythm of early morning reading and writing, a swim, a meal, repeat. But this morning, my laptop refused to start, and despite the best efforts of Apple support, refused again and again.

On my own for a few days, I was startled to discover how bereft I felt–the laptop has been my workhorse, my tool. I read and write largely on my laptop. I didn’t even bring a notebook. But I gave up, went to the ocean for a long walk by the wonderfully crashing stormy waves, came back, and miraculously, it’s working again.

On my own for a few days, I was startled to discover how bereft I felt–the laptop has been my workhorse, my tool. I read and write largely on my laptop. I didn’t even bring a notebook. But I gave up, went to the ocean for a long walk by the wonderfully crashing stormy waves, came back, and miraculously, it’s working again.

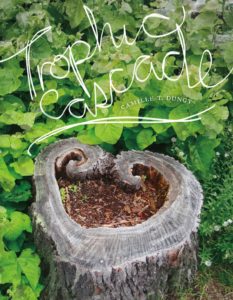

I can get back to work, and am publishing this wonderful poem by Camille Dungy a day early, in case this respite is temporary.

Trophic Cascade

After the reintroduction of gray wolves

to Yellowstone and, as anticipated, their culling

of deer, trees grew beyond the deer stunt

of the mid century. In their up reach

songbirds nested, who scattered

seed for underbrush, and in that cover

warrened snowshoe hare. Weasel and water shrew

returned, also vole, and came soon hawk

and falcon, bald eagle, kestrel, and with them

hawk shadow, falcon shadow. Eagle shade

and kestrel shade haunted newly-berried

runnels where mule deer no longer rummaged, cautious

as they were, now, of being surprised by wolves. Berries

brought bear, while undergrowth and willows, growing

now right down to the river, brought beavers,

who dam. Muskrats came to the dams, and tadpoles.

Came, too, the night song of the fathers

of tadpoles. With water striders, the dark

gray American dipper bobbed in fresh pools

of the river, and fish stayed, and the bear, who

fished, also culled deer fawns and to their kill scraps

came vulture and coyote, long gone in the region

until now, and their scat scattered seed, and more

trees, brush, and berries grew up along the river

that had run straight and so flooded but thus dammed,

compelled to meander, is less prone to overrun. Don’t

you tell me this is not the same as my story. All this

life born from one hungry animal, this whole,

new landscape, the course of the river changed,

I know this. I reintroduced myself to myself, this time

a mother. After which, nothing was ever the same.

Camille Dungy

From the book, Trophic Cascade, Wesleyan University Press, 2018

Citrus Freeze

Citrus Freeze The Necessity for Irony

The Necessity for Irony You are my friend–

You are my friend– The Moon

The Moon What Would I Do White?

What Would I Do White? The world of poetry is expanding to include new voices and new forms. It can be daunting, but also energizing. Here is a poem from a poet new to me whose work came to me online. I remember those fox stoles, my mother had one–something you’d never see today, but fascinating to me as a child. I love the descriptions in this poem and the way the rhythm of the poem matches the experience.

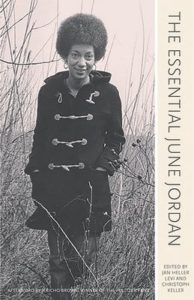

The world of poetry is expanding to include new voices and new forms. It can be daunting, but also energizing. Here is a poem from a poet new to me whose work came to me online. I remember those fox stoles, my mother had one–something you’d never see today, but fascinating to me as a child. I love the descriptions in this poem and the way the rhythm of the poem matches the experience. There’s a new selection of June Jordan’s poetry out, The Essential June Jordan. Here is a short sample–a poem I love for so many reasons, not least because of the way the complexity of title plays against the simplicity of the poem:

There’s a new selection of June Jordan’s poetry out, The Essential June Jordan. Here is a short sample–a poem I love for so many reasons, not least because of the way the complexity of title plays against the simplicity of the poem: On my own for a few days, I was startled to discover how bereft I felt–the laptop has been my workhorse, my tool. I read and write largely on my laptop. I didn’t even bring a notebook. But I gave up, went to the ocean for a long walk by the wonderfully crashing stormy waves, came back, and miraculously, it’s working again.

On my own for a few days, I was startled to discover how bereft I felt–the laptop has been my workhorse, my tool. I read and write largely on my laptop. I didn’t even bring a notebook. But I gave up, went to the ocean for a long walk by the wonderfully crashing stormy waves, came back, and miraculously, it’s working again. I reviewed Forrest Gander’s recent book,

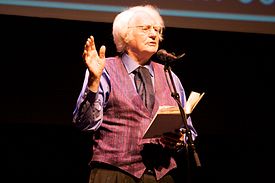

I reviewed Forrest Gander’s recent book,  I love this form that tells a story but is more than a story. When it works, it really works, as this, by Robert Bly:

I love this form that tells a story but is more than a story. When it works, it really works, as this, by Robert Bly: This has been a week a travel, visiting family and childhood friends I haven’t seen since before the lockdown. Often the part of our catching up is about health, what one friend calls “the organ recital.” This poem, then, feels appropriate:

This has been a week a travel, visiting family and childhood friends I haven’t seen since before the lockdown. Often the part of our catching up is about health, what one friend calls “the organ recital.” This poem, then, feels appropriate: What makes a paragraph a prose poem? Hard to say… The first one I posted remains one of my favorites,

What makes a paragraph a prose poem? Hard to say… The first one I posted remains one of my favorites,