I was so impressed by The Fire Next Time, which I finished today, that I have to quote a few more passages.

I was so impressed by The Fire Next Time, which I finished today, that I have to quote a few more passages.

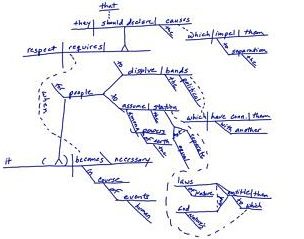

This after Baldwin’s meeting with Elijah Muhammad, talking in the car to a young follower about the idea of black nation separating from the United States:

“On what, then, will the economy of this separate nation be based? The boy gave me a rather strange look. I said hurriedly, ‘I’m not saying it can’t be done–I just want to know how it is to be done.’ I was thinking, In order for this to happen, your entire frame of reference will have to change, and you will be forced to surrender many things that you now scarcely know you have. I didn’t feel that the things I had in mind, such as the pseudo-elegant heap of tin in which we were riding, had any very great value. But life would be very different without them, and I wondered if he had though of this.”

Later:

“If one is permitted to treat any group of people with special disfavor because of their race or the color of their skin, there is no limit to what one will force them to endure, and since the entire race has been mysteriously indicted, no reason not to attempt to destroy it root and branch. This is precisely what the Nazis attempted. Their only originality lay in the means they used. It is scarcely worthwhile to attempt remembering ow many times the sun has looked down on the slaughter of the innocents. I am very much concerned that American Negroes achieve their freedom here in the United States. But I am also concerned for their dignity, for the health of their souls, and must oppose any attempt that Negroes may make to do to others what has been done to them. I think I know–we see it around us every day–the spiritual wasteland to which that road leads. It is so simple a fact and one that is so hard, apparently, to grasp: Whoever debases others is debasing himself. That is not a mystical statement, but a most realistic one, which is proved by the eyes of any Alabama sheriff–and I would not like to see Negroes ever arrive at so wretched a condition… Continue reading “More Baldwin: Whoever debases others is debasing himself”

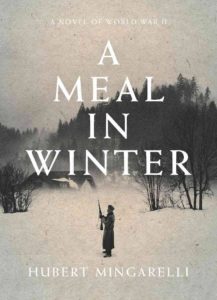

This extraordinary little book is told as if a memoir, in very straightforward, matter-or-fact prose, which makes it all the more chilling. It is translated from the French by Sam Taylor. The basic plot concerns three German soldiers who no longer want to shoot Jews. They go to the commander, who is “a reservist like we were”:

This extraordinary little book is told as if a memoir, in very straightforward, matter-or-fact prose, which makes it all the more chilling. It is translated from the French by Sam Taylor. The basic plot concerns three German soldiers who no longer want to shoot Jews. They go to the commander, who is “a reservist like we were”: