I’ve been reading Adam Zagajewski’s recent book of poetry, Unseen Hand, translated by Clare Cavanagh. Zagajewski writes in Polish, and I’ve long admired his work.

I encountered this poem of his just after I had reread a poem of Larry’s about envisioning his mother’s funeral. Yes, Larry, too is a poet. His poem is from his book called Night Train. Here are the two:

About My Mother

About My Mother

I could never say anything about my mother:

how she repeated, you’ll regret it one day,

when I’m not around anymore, and how I didn’t believe

in either “I’m not” or “anymore,”

how I liked watching as she read bestsellers,

always turning to the last chapter first,

how in the kitchen, convinced it wasn’t

her proper place, she made Sunday coffee,

or even worse, filet of cod,

how she studied the mirror while expecting guests,

making the face that best kept her

from seeing herself as she was ( I take

after her in this and other failings),

how she went on at length about things

that weren’t her strong suit and how I stupidly

teased her, for example when she

compared herself to Beethoven going deaf,

and I said, cruelly, but you know he

had talent, and how she forgave it all

and how I remember that, and how I flew from Houston

to her funeral and couldn’t say anything

and still can’t.

Adam Zagajewski, translated by Clare Cavanagh

***************************

When I go to your funeral

When I go to your funeral

I’ll be clean-shaven & have

a fresh haircut. I’ll wear

a black silk tie with a Windsor

knot, a charcoal-grey suit

(3-buttoned, with vest).

My socks will match.

My shoes will be shined.

I’ll look real sharp, Mom.

And everyone will murmur

“now there’s a young man

with promise” & everything

will be like it once was—

before the pulleys creak

& the ropes slowly lower

your coffin out of the red

clay granite sunshine

of western Oaklahoma.

Larry Rafferty

I think Larry stands up pretty well with Zagajewski, although I have to admit that the lines:

how she studied the mirror while expecting guests,

making the face that best kept her

from seeing herself as she was

are pretty breathtaking in their unsparing appraisal. I’m just glad I wasn’t Mr. Zagajewski’s mother! As for Larry, well, I’m his wife and have often felt that unsparing, appraising eye–but tempered with fondness.

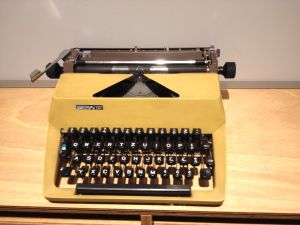

It’s been awhile since I published a prose piece. This snippet is from

It’s been awhile since I published a prose piece. This snippet is from  When we were in Krakow a few years ago (sadly we missed Lesser Wółka), there was a museum show called

When we were in Krakow a few years ago (sadly we missed Lesser Wółka), there was a museum show called