How lucky to live in the Bay Area, with its surfeit of poetry events. Today, I heard Bob Hass talk about and read from the work of Tomas Tranströmer and Czesław Miłosz. The one-hour event is from a series at UC called “Lunch Poems,” and was billed as Hass reading from the work of Miłosz. News had just come in that Tranströmer had won the Nobel Prize and Bob talked about and read a few of his poems, too. He has translated both poets, and said that the three of them once had a meal together in Paris.

How lucky to live in the Bay Area, with its surfeit of poetry events. Today, I heard Bob Hass talk about and read from the work of Tomas Tranströmer and Czesław Miłosz. The one-hour event is from a series at UC called “Lunch Poems,” and was billed as Hass reading from the work of Miłosz. News had just come in that Tranströmer had won the Nobel Prize and Bob talked about and read a few of his poems, too. He has translated both poets, and said that the three of them once had a meal together in Paris.

It was wonderful to hear Bob’s exposition on both these poets. I don’t have copies of exactly the poems he read, but soon the reading and Bob stories will be on YouTube, you can search for it. In the meantime, here is a famous poem by Miłosz, who lived in exile from his native country for several decades in Berkeley. Until he received the Nobel Prize in 1980, he was almost unknown here, a professor of Polish literature at UC, writing in Polish, not largely translated.

This poem is fairly typical, starting with an event, seeming to meander along, almost prose, in reminiscence. The “magic mountain” itself is a reference to Tomas Mann’s novel by that name, about a man exiled to a sanitorium for tuberculosis. But as the poem meanders it gathers to a fierce anger–the poet blazes out at his lack of recognition, the absence of fame, his inability to change the world. From there it moves to acceptance, endurance, and a wonderful couplet about how the work of poetry itself is a kind of salvation:

With a flick of the wrist I fashioned an invisible rope,

And climbed it and it held me.

Then, the poet is back in the real world, a little self-mocking, a little disdaining of the pomp of caps and gowns. He returns to July in Berkeley, hummingbirds and fog. It must have been hard for a poet whose work over and over seems extraordinarily alive to place to have lived most of his life estranged from home.

A Magic Mountain

I don’t remember exactly when Budberg died, it was either two years

ago or three.

The same with Chen. Whether last year or the one before.

Soon after our arrival, Budberg, gently pensive,

Said that in the beginning it is hard to get accustomed,

For here there is no spring or summer, no winter or fall.

“I kept dreaming of snow and birch forests.

Where so little changes you hardly notice how time goes by.

This is, you will see, a magic mountain.”

Budberg: a familiar name in my childhood.

They were prominent in our region,

This Russian family, descendants of German Balts.

I read none of his works, too specialized.

And Chen, I have heard, was an exquisite poet,

Which I must take on faith, for he wrote in Chinese.

Sultry Octobers, cool Julys, trees blossom in February.

Here the nuptial flight of hummingbirds does not forecast spring.

Only the faithful maple sheds its leaves every year.

For no reason, its ancestors simply learned it that way.

I sensed Budberg was right and I rebelled.

So I won’t have power, won’t save the world?

Fame will pass me by, no tiara, no crown?

Did I then train myself, myself the Unique,

To compose stanzas for gulls and sea haze,

To listen to the foghorns blaring down below?

Until it passed. What passed? Life.

Now I am not ashamed of my defeat.

One murky island with its barking seals

Or a parched desert is enough

To make us say: yes, oui, si.

“Even asleep we partake in the becoming of the world.”

Endurance comes only from enduring.

With a flick of the wrist I fashioned an invisible rope,

And climbed it and it held me.

What a procession! Quelles délices!

What caps and hooded gowns!

Most respected Professor Budberg,

Most distinguished Professor Chen,

Wrong Honorable Professor Milosz

Who wrote poems in some unheard-of tongue.

Who will count them anyway. And here sunlight.

So that the flames of their tall candles fade.

And how many generations of hummingbirds keep them company

As they walk on. Across the magic mountain.

And the fog from the ocean is cool, for once again it is July.

Berkeley, 1975

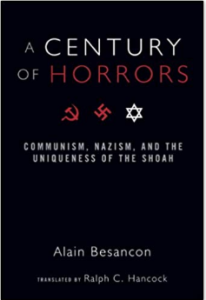

I know that you’re supposed to take up some frivolous books for the summer, but perhaps influenced by the morning and evening fog that characterizes coastal California, my reading has been more dour. I mentioned these books in an earlier post: A Century of Horrors, by Alain Besançon, Hope Against Hope, by Osip Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, and most of Secondhand Time (I couldn’t get through all of it), by Svetlana Alexievich. I also just reread Czesław Miłosz’ The Captive Mind. All of these books deal with the phenomenon of Communism as it has been practiced since the Russian Revolution. Besançon’s thesis is that while Nazism was horrific, it was a brief nightmare compared to Communism. The Shoah was intense, killed millions, but was defeated and rejected.

I know that you’re supposed to take up some frivolous books for the summer, but perhaps influenced by the morning and evening fog that characterizes coastal California, my reading has been more dour. I mentioned these books in an earlier post: A Century of Horrors, by Alain Besançon, Hope Against Hope, by Osip Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, and most of Secondhand Time (I couldn’t get through all of it), by Svetlana Alexievich. I also just reread Czesław Miłosz’ The Captive Mind. All of these books deal with the phenomenon of Communism as it has been practiced since the Russian Revolution. Besançon’s thesis is that while Nazism was horrific, it was a brief nightmare compared to Communism. The Shoah was intense, killed millions, but was defeated and rejected.