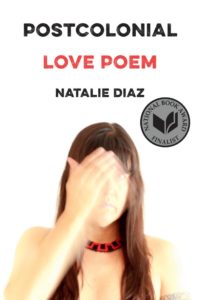

I know I’ve posted something from her book, Post-Colonial Love Poem, but I came across this one recently and love the sensuality in contrast to the landscape and car details.

If I Should Come Upon Your House Lonely in the West Texas Desert

I will swing my lasso of headlights

across your front porch,

let it drop like a rope of knotted light

at your feet.

While I put the car in park,

you will tie and tighten the loop

of light around your waist —

and I will be there with the other end

wrapped three times

around my hips horned with loneliness.

Reel me in across the glow-throbbing sea

of greenthread, bluestem prickly poppy,

the white inflorescence of yucca bells,

up the dust-lit stairs into your arms.

If you say to me, This is not your new house

but I am your new home,

I will enter the door of your throat,

hang my last lariat in the hallway,

build my altar of best books on your bedside table,

turn the lamp on and off, on and off, on and off.

I will lie down in you.

Eat my meals at the red table of your heart.

Each steaming bowl will be, Just right.

I will eat it all up,

break all your chairs to pieces.

If I try running off into the deep-purpling scrub brush,

you will remind me,

There is nowhere to go if you are already here,

and pat your hand on your lap lighted

by the topazion lux of the moon through the window,

say, Here, Love, sit here — when I do,

I will say, And here I still am.

Until then, Where are you? What is your address?

I am hurting. I am riding the night

on a full tank of gas and my headlights

are reaching out for something.

Natalie Diaz

originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine (April 1, 2021).

I have just finished reading Natalie Diaz’ first book, My Brother Was an Aztec. The poems are powerful, the imagery lush and unusual, but the subject matter–addiction, pain, the struggle with family and poverty–is told in unsparing detail. So I thought I’d start of 2020, a year that itself promises to be harsh, with one of her poems from the book:

I have just finished reading Natalie Diaz’ first book, My Brother Was an Aztec. The poems are powerful, the imagery lush and unusual, but the subject matter–addiction, pain, the struggle with family and poverty–is told in unsparing detail. So I thought I’d start of 2020, a year that itself promises to be harsh, with one of her poems from the book: