Tag: prose poem

Prose poem

What makes a paragraph a prose poem? Hard to say… The first one I posted remains one of my favorites, A Story about the Body, by Robert Hass. It does tell a story, but it’s more than a story. This one, by Tom Hennen, starts out simply as prose, but then goes somewhere else.

What makes a paragraph a prose poem? Hard to say… The first one I posted remains one of my favorites, A Story about the Body, by Robert Hass. It does tell a story, but it’s more than a story. This one, by Tom Hennen, starts out simply as prose, but then goes somewhere else.

Report from the West

Snow is falling west of here. The mountains have more than a

foot of it. I see the early morning sky dark as night. I won’t lis-

ten to the weather report. I’ll let the question of snow hang.

Answers only dull the senses. Even answers that are right often

make what they explain uninteresting. In nature the answers

are always changing. Rain to snow, for instance. Nature can

let the mysterious things alone—wet leaves plastered to tree

trunks, the intricate design of fish guts. The way we don’t fall

off the earth at night when we look up at the North Star. The

way we know this may not always be so. The way our dizziness

makes us grab the long grass, hanging by our fingertips on the

edge of infinity.

Tom Hennen, “Report from the West” from Darkness Sticks to Everything: Collected and New Poems.

Psychics

There was a time in my life when I wanted very much to know the future. I went to many psychic readers of various kinds, from carnival tents, to very “serious” future tellers. As it is now, one day at a time is enough!

There was a time in my life when I wanted very much to know the future. I went to many psychic readers of various kinds, from carnival tents, to very “serious” future tellers. As it is now, one day at a time is enough!

Still, I really loved this prose poem, and wish you all the white light of Alma, which in my time of psychics they called simply “white light.”

The Psychic

He said I must pay special attention in cars. He wasn’t, he assured me, saying that I’d be in an accident but that for two weeks some particular caution was in order, &, he said, all I really needed to do was throw the white light of Alma around any car I entered & then I’d be fine. & when I asked about Alma, he said, Oh, come on, you know Alma well. You two were together first in Egypt & then at Stonehenge, & I nodded though I’ve never been— in this life at least—to Stonehenge; then I said, Shouldn’t I always throw the white light of Alma around a car? & when he said, Well, it wouldn’t hurt, I said, What about around planes, houses? What if I throw the white light of Alma around anyone who might need protection from the reckless speed of driving or the reckless swerve & skid of the world? & the psychic opened his hands & shrugged up his shoulders. So despite your doubt or mine as to why I’d gone there, to a psychic, in—I kid you not—a town of psychics—in the first place, right now, as you read this, let me throw the white light of Alma around you & everyone you pass close to today, beloved or stranger, the grocer, the bus driver, the boy on his longboard, the lady you stand silent beside in the elevator, & also I am throwing it around anyone they care about anywhere in the spin of the world, because, we can agree that these days, everywhere, particular caution is in order &, even if unverifiable, the light of my dear sister Alma, couldn’t hurt.

One more prose poem

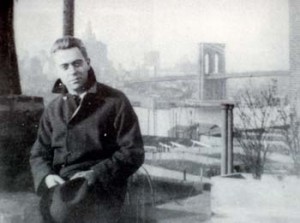

This one is from Mark Ford’s Selected Poems published by Coffee House Press (2014). Mark said this is the only prose poem he’s ever written. If, like me, you’re a fan of Hart Crane, it’s especially delicious. It’s in the form of a letter to a fictitious literary magazine. If you know nothing about Hart Crane, here is his most famous poem, To Brooklyn Bridge. A tortured gay man, who lived in a time when that was unacceptable, he allegedly committed suicide at 33 by jumping off a ship returning to New York from Mexico.

This one is from Mark Ford’s Selected Poems published by Coffee House Press (2014). Mark said this is the only prose poem he’s ever written. If, like me, you’re a fan of Hart Crane, it’s especially delicious. It’s in the form of a letter to a fictitious literary magazine. If you know nothing about Hart Crane, here is his most famous poem, To Brooklyn Bridge. A tortured gay man, who lived in a time when that was unacceptable, he allegedly committed suicide at 33 by jumping off a ship returning to New York from Mexico.

The Death of Hart Crane

Sir / Madam,

I was intrigued by the letter from a reader in your last issue that recounted his meeting, in a bar in Greenwich Village in the mid-sixties, a woman who claimed to have been a passenger on the Orizaba on the voyage the boat made from Vera Cruz to New York in April of 1932, a voyage that the poet Hart Crane never completed. According to her Crane was murdered and thrown overboard by sailors after a night of such rough sex that they became afraid (surely wrongly) that he might have them arrested when the boat docked in Manhattan. This reminded me of a night in the early seventies on which I too happened to be drinking in a bar in Greenwich Village. I got talking to an elderly man called Harold occupying an adjacent booth, and when the conversation touched on poetry he explained, somewhat shyly, that he had himself published two collections a long time ago, one called White Buildings in 1926, and the other, The Bridge, in 1930. I asked if he’d written much since. ‘Oh plenty,’ he replied, ‘and a lot of it much better than my early effusions.’ I expressed an interest in seeing this work, and he invited me back to his apartment on MacDougal Street. Here the evening turns somewhat hazy. I could hear the galloping strains of Ravel’s Boléro turned up loud as Harold fumbled for his keys. Clearly some sort of party was in progress. At that moment the door was opened from within by another man in his seventies, who exclaimed happily, ‘Hart! – and friend! Come in!’ The room was full of men in their seventies, all, or so it seemed, called either Hart or Harold. The apartment’s walls were covered with Aztec artefacts, and its floors with Mexican carpets. It dawned on me then that Hart Crane had not only somehow survived his supposed death by water, but that his vision of an America of the likeminded was being fulfilled that very night, as it was perhaps every night, in this apartment on MacDougal Street. At the same instant I realized that it was I, an absurd doubting Thomas brought face to face with a miracle, who deserved to be devoured by sharks.

Yours faithfully,

Name and address withheld

by Mark Ford