The turkey’s strung up by one pronged foot,

the cord binding it just below the stiff trinity

of toes, each with its cold bent claw. My eyes

are in love with it as they are in love with all

dead things that cannot escape being looked at.

It is there to be seen if I want to see it, as my

father was there in his black casket and could not

elude our gaze. I was a child so they asked

if I wanted to see him. “Do you want to see him?”

someone asked. Was it my mother? Grandmother?

Some poor woman was stuck with the job.

“He doesn’t look like himself,” whoever-it-was

added. “They did something strange with his mouth.”

As I write this, a large moth flutters against

the window. It presses its fat thorax to the glass.

“No,” I said, I don’t want to see him.” I don’t recall

if I secretly wanted them to open the box for me

but thought that “no” was the correct response,

or if I believed I should want to see him but was

too afraid of what they’d done with his mouth.

I think I assumed that my seeing him would

make things worse for my mother, and she was allI had.

Now I can’t get enough of seeing, as if I’m paying

a sort of penance for not seeing then, and so

this turkey, hanged, its small, raw-looking head,

which reminds me of the first fully naked man

I ever saw, when I was a candy striper

at a sort of nursing home, he was a war veteran,

young, burbling crazily, his face and body red

as something scalded. I didn’t want to see,

and yet I saw. But the turkey, I am in love with it,

its saggy neck folds, the rippling, variegated

feathers, the crook of its unbound foot,

and the glorious wings, archangelic, spread

as if it could take flight, but down,

downward, into the earth.

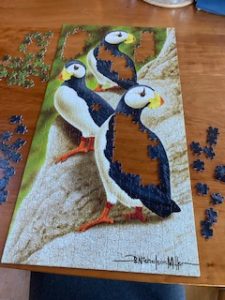

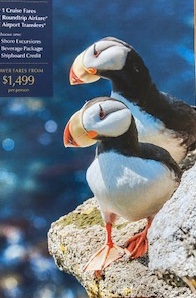

This weekend I had my grandsons overnight and broke out the Puffin puzzle, which we had a lot of fun with, but didn’t finish. Then the Sunday NY Times arrived, with a brochure for cruise ships. It had this image on the cover.

This weekend I had my grandsons overnight and broke out the Puffin puzzle, which we had a lot of fun with, but didn’t finish. Then the Sunday NY Times arrived, with a brochure for cruise ships. It had this image on the cover.