This is a line from Mirele Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto, written in 1969. Part of the avant-guard art scene in New York in the sixties, after having her first child she noticed there was no time for art–only maintenance: diapers, cooking, cleaning, dressing, undressing. The basic idea of the manifesto is that maintenance is art. You can see the full Manifesto here. It includes these intriguing paragraphs.

This is a line from Mirele Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto, written in 1969. Part of the avant-guard art scene in New York in the sixties, after having her first child she noticed there was no time for art–only maintenance: diapers, cooking, cleaning, dressing, undressing. The basic idea of the manifesto is that maintenance is art. You can see the full Manifesto here. It includes these intriguing paragraphs.

“C. Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.)

The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom.

The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.

clean your desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor, wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the fence, keep the customer happy, throw out the stinking garbage, watch out don’t put things in your nose, what shall I wear, I have no sox, pay your bills, don’t litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets, go to the store, I’m out of perfume, say it again—he doesn’t understand, seal it again—it leaks, go to work, this art is dusty, clear the table, call him again, flush the toilet, stay young.

D. Art:

Everything I say is Art is Art. Everything I do is Art is Art. “We have no Art, we try to do everything well.” (Balinese saying)…

E. The exhibition of Maintenance Art, “CARE,” would zero in on pure maintenance, exhibit it as contemporary art, and yield, by utter opposition, clarity of issues.”

I was so intrigued by these ideas (having spent most of my adult life in Maintenance) that I came to New York to see her 50-year retrospective at the Queens Museum.

The photo above is of Ukeles standing inside an arch she created from used, signed workers gloves, walkie-talkies, subway straps, valves, lights, gauges, etc. It’s one of the more visceral pieces at the Queens Museum show. Because most of her work is performance pieces–washing a stage or floor or wall and engaging others to participate, a ballet of sanitation trucks or snow blowers or other heavy equipment, a piece where she invited workers to see one of their eight hours of work as maintenance art and photographed them–much of the work is shown as video or photo with documentation.

The photo above is of Ukeles standing inside an arch she created from used, signed workers gloves, walkie-talkies, subway straps, valves, lights, gauges, etc. It’s one of the more visceral pieces at the Queens Museum show. Because most of her work is performance pieces–washing a stage or floor or wall and engaging others to participate, a ballet of sanitation trucks or snow blowers or other heavy equipment, a piece where she invited workers to see one of their eight hours of work as maintenance art and photographed them–much of the work is shown as video or photo with documentation.

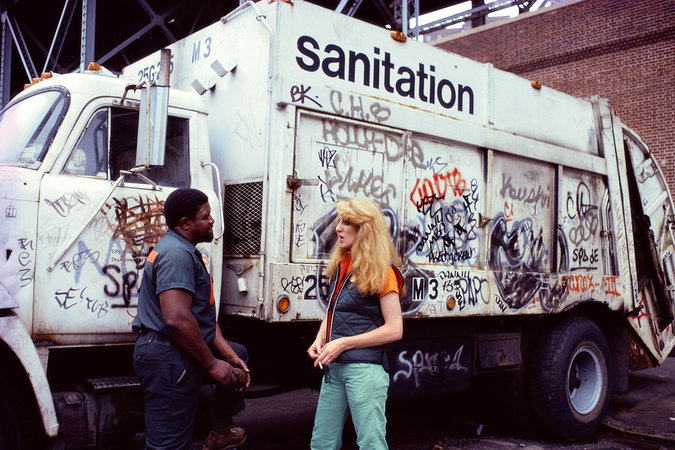

In 1977, Ukeles became the artist in residence for the New York Department of Sanitation. Although her residency was unpaid, the title gave her a platform to conceive and find funding for a wide variety of projects. In her project Touch Sanitation she went to all five boroughs to shake the hands, thank, and talk with every one of NYC’s 8500 sanitation workers.

Other projects, such as a visual bridge of recycled materials overlooking the dumping of garbage onto barges at the 59th street pier, were never funded.

Other projects, such as a visual bridge of recycled materials overlooking the dumping of garbage onto barges at the 59th street pier, were never funded.

Recently, she has been engaged in the transformation of garbage “our garbage, not their garbage.” She has created hallways of recycled garbage, videos of the garbage process and proposed radical redesigns for expired garbage dumps, most notably Fresh Kills, on Staten Island.

Her ideas about the invisibility of maintenance workers, maintenance art as revolutionary, and garbage as an essential concern of art seem visionary to me. I’m only sorry that I won’t get to meet her in February, when she will lead a tour of the Fresh Kills project.