One of the most moving visits for me in St. Petersburg was the trip to the Akhmatova Museum. For many years Akhmatova lived in rooms assigned to her in the former Sheremetev Palace, which was collectivized after the revolution and made into apartments. During this time, her son and second husband both endured varying prison sentences and she was forced to write poetry in praise of Stalin to hope to secure their release. Here’s a short quote from Wikipedia:

One of the most moving visits for me in St. Petersburg was the trip to the Akhmatova Museum. For many years Akhmatova lived in rooms assigned to her in the former Sheremetev Palace, which was collectivized after the revolution and made into apartments. During this time, her son and second husband both endured varying prison sentences and she was forced to write poetry in praise of Stalin to hope to secure their release. Here’s a short quote from Wikipedia:

“…the authorities had bugged her flat and kept her under constant surveillance, keeping detailed files on her from this time, accruing some 900 pages of “denunciations, reports of phone taps, quotations from writings, confessions of those close to her”. Although officially stifled, Akhmatova’s work continued to circulate in secret, her work hidden, passed and read in the gulags...A small trusted circle would, for example, memorise each other’s works and circulate them only by oral means. She tells how Akhmatova would write out her poem for a visitor on a scrap of paper to be read in a moment, then burnt in her stove. The poems were carefully disseminated in this way, however it is likely that many complied in this manner were lost. “It was like a ritual,” Chukovskaya wrote. “Hands, matches, an ashtray. A ritual beautiful and bitter.”

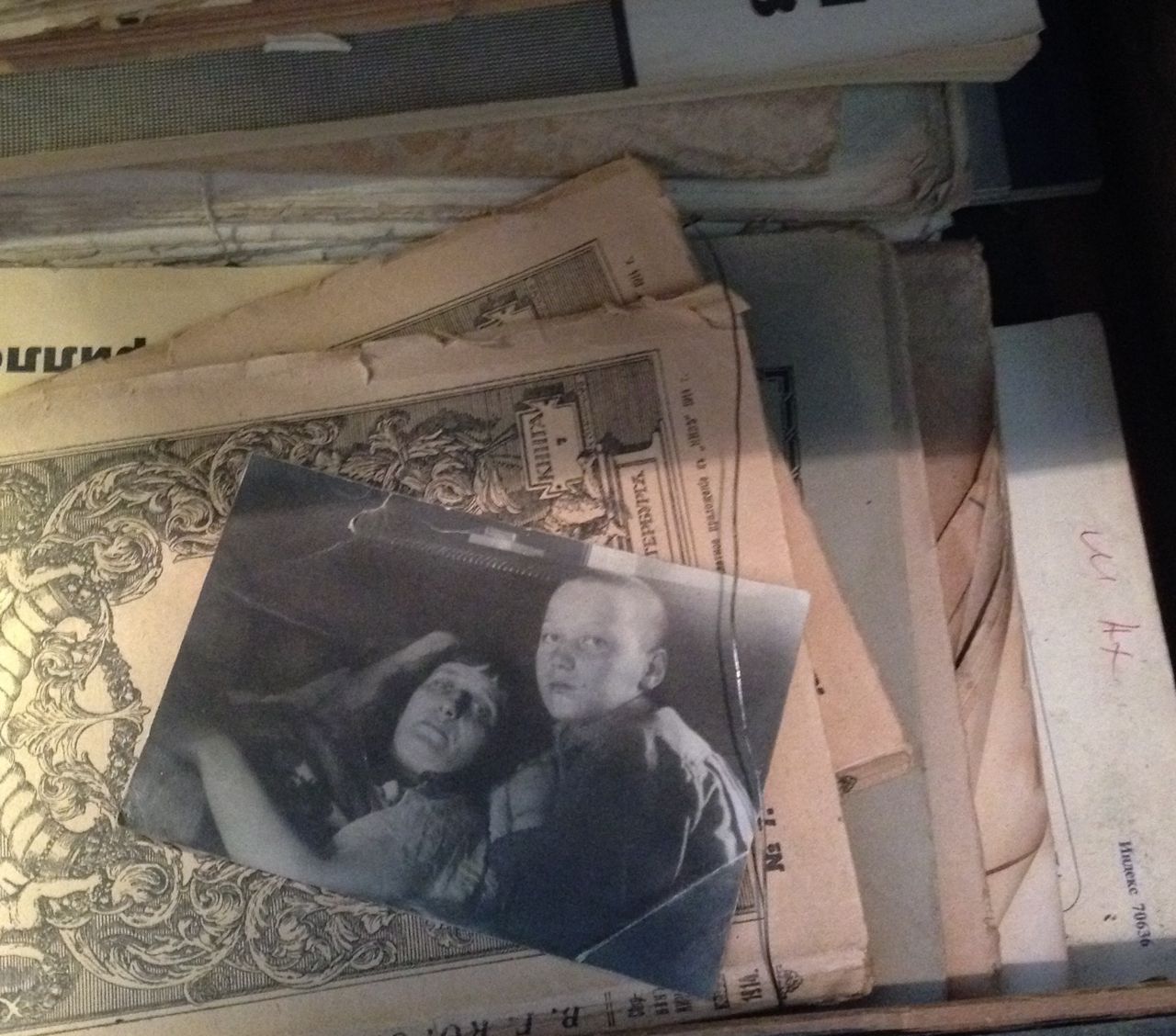

You could feel this atmosphere in the rooms. I was moved by the spareness of her apartment, the photo of her and her son, manuscript pages, and above all her shapeless coat hanging in the entryway. At least the view from her window was a tree-filled courtyard.

A group of students was in the flat while we were there, being bored by their teacher who was droning on in Russian. Just before we left, I screwed up my courage and politely interrupted her in Russian to ask if they’d like to hear a very short poem by Akhmatova. She wasn’t happy about it. But I recited it anyway. You can hear Akhmatova herself recite it here.

Here’s the English:

Ah, but I am warning you

This life’s the last I’m living through.

Not as a swallow, or a poplar

Not as a reed or a star,

Not as water from a spring

Nor a bell’s hollow song—

I won’t return to trouble men

Or visit stranger’s dreams again

With my unquenchable lament.

After the museum, we went by the Stray Dog Cafe, not a long walk from her apartment, to talk about terms for the book. We were shown the original cafe, behind the rooms we had seen before, and the table toward the front where Akhmatova used to sit.

A